CoC vs. IRR: Key Differences for Startup Investors

Cash-on-Cash Return (CoC) and Internal Rate of Return (IRR) are two critical metrics for evaluating startup investments. They serve different purposes and provide unique insights into performance:

CoC measures the total cash returned compared to the initial investment. It’s simple and focuses on absolute returns, often expressed as a multiple (e.g., 3×). However, it doesn’t consider the timing of returns.

IRR calculates the annualized return while accounting for when cash flows occur. It’s better for comparing investments with varying timeframes or cash flow structures, but involves more complex calculations.

Key Takeaways:

Use CoC for assessing total wealth created.

Use IRR to measure time-adjusted efficiency.

Combine both for a complete view of performance.

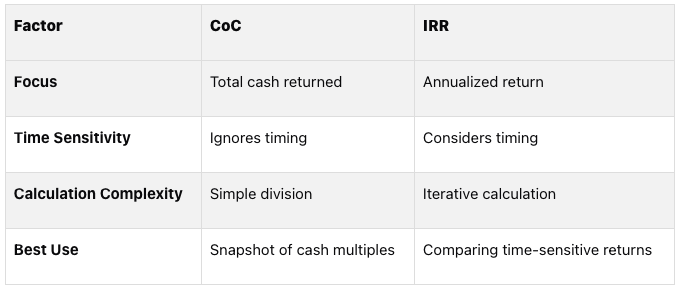

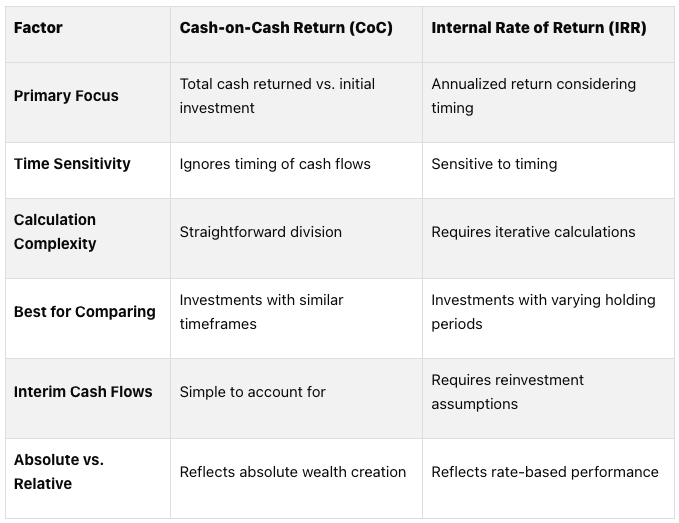

Here’s a quick comparison table:

For startup investors, knowing when to use CoC, IRR, or both can lead to smarter decisions and better portfolio management.

IRR vs. Cash on Cash Multiples in Leveraged Buyouts and Investments

What is Cash-on-Cash Return (CoC)

Cash-on-Cash Return (CoC) is a simple yet effective financial metric that startup investors use to evaluate the annual return on their actual cash investment. Unlike more intricate calculations that rely on various assumptions, CoC zeroes in on the cash you put in versus the cash you get back. This makes it a straightforward way to assess how well an investment generates cash flow [1][2].

Expressed as either a ratio or a percentage, CoC represents the annual pre-tax cash flow generated by an investment relative to the total cash invested. For instance, if you invest $100,000 and receive $15,000 in annual cash distributions, your CoC would be 15%. Importantly, this metric also reflects the role of financing leverage in boosting cash returns [8].

How CoC Works and Calculation Method

To calculate Cash-on-Cash Return, use this formula:

CoC = Annual Pre-Tax Cash Flow ÷ Total Cash Invested

In the context of startup investments, cash flows can differ significantly from traditional asset classes. For example, the annual pre-tax cash flow might come from periodic distributions during the investment period or from exit events like acquisitions or IPOs. In many venture capital scenarios, CoC is often expressed as a multiple rather than a percentage. A 4× CoC, for example, means you received four times your initial cash investment. While the presence of interim cash flows can make the calculation more complicated, the core idea remains the same: divide the actual cash received by the actual cash invested.

Benefits of Using CoC

One of CoC's biggest strengths is its focus on actual cash transactions. By avoiding assumptions about future valuations, it provides a clear and unambiguous snapshot of how efficiently cash is being generated. This makes it especially useful for evaluating cash flow performance when managing a startup portfolio.

Drawbacks of CoC

Despite its advantages, CoC has notable limitations. For one, it doesn't account for the time value of money. A 3× return achieved in two years is vastly different from the same return spread over ten years, yet CoC treats them as equal. This can make it less effective for comparing investments with varying time horizons, which is common in startup investing.

Additionally, CoC doesn't factor in the timing of cash flows - whether they come in multiple rounds or at different exit events. It also doesn't provide insights into risk-adjusted returns. For startups with complex capital structures, such as significant debt or intricate equity arrangements, CoC figures may not fully capture the underlying financial performance. In the next section, we'll delve into IRR to offer a complementary perspective.

What is Internal Rate of Return (IRR)

The Internal Rate of Return (IRR) measures the annualized return of an investment over its entire lifespan. Unlike Cash-on-Cash Return, which only looks at the total cash returned, IRR factors in when those cash flows happen. This makes it especially useful for startups, where cash flow timing can vary greatly.

IRR is essentially the discount rate that makes the net present value (NPV) of all cash flows from an investment equal to zero. Put simply, it’s the rate of return that balances the initial investment with the total cash flows received over time. For startup investors, IRR answers a key question: what annual return does this investment provide when we consider both the amount and the timing of cash flows?

What makes IRR so helpful is its ability to distill a multi-year investment into a single annual percentage. Whether you’re looking at a two-year exit or a seven-year holding period, IRR gives you a consistent way to evaluate and compare these different timelines.

Now, let’s break down how IRR works and how it’s calculated.

How IRR Works and Calculation Method

The formula for IRR looks like this:

0 = CF₀ + CF₁/(1+IRR)¹ + CF₂/(1+IRR)² + ... + CFₙ/(1+IRR)ⁿ

Here:

CF₀ is your initial investment (a negative value since it’s money going out).

CF₁ through CFₙ are the cash flows you receive in subsequent periods.

The goal is to find the IRR value that makes the NPV of all these cash flows zero. Since this calculation is iterative and can get complicated, most investors use tools like Excel’s IRR function or an online IRR calculator.

For example, say you invest $50,000 in a startup, and it returns $200,000 after four years. The IRR for this investment would be approximately 41.4%. This calculation adjusts for the fact that your money was tied up for four years, offering a clearer picture of the investment’s performance compared to just looking at the total return.

One important thing to note: investments with earlier cash returns will show a higher IRR than those with later returns - even if the total cash amount is the same.

Benefits of Using IRR

IRR offers several advantages, especially for startup investors and venture capitalists.

Its biggest strength is that it incorporates the time value of money, making it a powerful tool for comparing investments with different timelines or cash flow schedules. For instance, a 30% IRR achieved in three years can be directly compared to a 25% IRR achieved over five years - something that Cash-on-Cash Return can’t do.

IRR also handles the complexities of startup investing well. Whether you’re dealing with interim distributions, dividends, or multiple rounds of follow-on investments, IRR can accommodate these varied cash flow patterns in a single calculation.

For portfolio management, IRR allows investors to rank opportunities based on time-sensitive, risk-adjusted returns. This is especially useful when weighing different investment options or evaluating fund managers and strategies.

Additionally, IRR serves as a standardized benchmark. For example, if a startup investment shows a 25% IRR, you can directly compare it to returns from public markets, real estate, or other alternative investments to gauge its relative performance.

Drawbacks of IRR

While IRR is a sophisticated metric, it’s not without its flaws.

One challenge is its complexity. For investments with irregular cash flows, the calculation can be difficult to interpret. In some cases, you might even end up with multiple IRR solutions, especially if cash flows alternate between positive and negative, leading to confusion.

Another limitation is that IRR assumes any interim cash flows can be reinvested at the same IRR rate. For example, if your startup investment generates a 40% IRR, the calculation assumes you can reinvest those distributions at the same 40% rate. In reality, finding similar high-return opportunities can be tough.

IRR can also be misleading for investments with short-term, high returns. For instance, a small investment that doubles quickly might show an inflated IRR, but that doesn’t necessarily reflect skill or a sustainable strategy. It’s just the math making the return look better than it might actually be.

Liquidity also plays a critical role when assessing IRR. For example, we observed firsthand in 2021 hundreds of startups and VC funds with frequent and significant valuation markups, which juiced IRR and enabled GPs to raise larger and more frequent funds. However, no actual cash was returned to investors, and those paper gains were later marked down during the 2022 crash.

For startups that don’t generate interim cash flows - since many reinvest profits for growth - IRR relies heavily on exit events. This limits its usefulness for ongoing performance evaluation during the investment period.

Lastly, IRR doesn’t consider the absolute size of returns. A $10,000 investment with a 50% IRR may look better on paper than a $100,000 investment with a 30% IRR. However, the larger investment generates significantly more wealth in absolute terms, which IRR alone doesn’t capture.

Main Differences Between CoC and IRR

Cash-on-Cash Return (CoC) and Internal Rate of Return (IRR) are both essential tools for evaluating startup investments, but they serve very different purposes. Each metric provides unique insights, and knowing when to use one over the other can significantly influence investment decisions.

The primary distinction lies in their focus. CoC measures the total cash multiple you receive, without considering the timing of returns. On the other hand, IRR emphasizes the annualized return, factoring in when cash flows occur. This difference becomes crucial when comparing investments with varying holding periods or cash flow structures.

Side-by-Side Comparison: CoC vs. IRR

Here’s an example to illustrate the difference: Imagine two startup investments. Investment A turns a $100,000 investment into $300,000 in two years, while Investment B produces the same $300,000 return from a $100,000 investment, but over five years. Using CoC, both investments show a 3× return. However, IRR paints a clearer picture of efficiency - Investment A has an annualized return of about 73.2%, while Investment B’s annualized return is only 24.6%. This demonstrates how IRR can highlight the impact of timing, which CoC overlooks.

This distinction also plays out in real-world scenarios. For example, IRR is particularly useful for comparing opportunities across different stages, like weighing a Series A investment with a three-year exit against a seed-stage investment that takes seven years to mature. Meanwhile, CoC’s simplicity makes it a great tool for quickly assessing absolute returns, especially in portfolio reviews.

How to Choose Between CoC and IRR

Choosing the right metric depends on the specific insights you’re seeking.

Use CoC when you want to understand the absolute wealth creation potential of an investment or when comparing opportunities with similar holding periods.

Use IRR when comparing investments with different timeframes or when benchmarking against other asset classes to guide allocation decisions.

Use both together for a complete picture: CoC shows how much wealth an investment can generate, while IRR evaluates how efficiently time and capital are utilized.

Your investment strategy also plays a role. Growth equity investors, who typically hold positions for three to seven years, often rely on IRR to evaluate opportunities across stages and sectors. On the other hand, venture capital investors may lean toward CoC for assessing absolute return potential in specialized scenarios.

Ultimately, the choice boils down to the question you’re trying to answer. Each metric offers unique insights, and using the right one - or both - can provide the clarity needed to make informed investment decisions.

How to Use CoC and IRR in Practice

Knowing when and how to apply CoC (Cash-on-Cash) and IRR (Internal Rate of Return) can simplify complex investment decisions. Each metric serves a unique purpose, depending on your goals, timeline, and the nature of the investment opportunities. By understanding their practical applications, you can choose the right tool for evaluating your investments.

Best Times to Use CoC

CoC is ideal for illustrating absolute returns and is often used when the timing of returns isn't the primary concern. For instance, VC fund managers frequently rely on CoC when reporting to limited partners after liquidity events. It clearly shows how much cash was generated compared to the initial investment.

Year-end portfolio reviews are another scenario where CoC shines. It provides a clear snapshot of which investments delivered the highest absolute returns. Let’s say you invested $50,000 in a fintech startup that was later acquired for $200,000. A 4× CoC demonstrates, in simple terms, the wealth created through that investment.

CoC is also helpful when comparing investments at similar stages within the same timeframe. For example, if you're evaluating two seed-stage opportunities with expected exits in three to four years, CoC allows you to focus solely on the return potential. It’s particularly useful for quick assessments, helping you identify your top-performing investments at a glance.

Angel investors often prefer CoC because it answers the straightforward question: "How much did I make?" This simplicity makes it easier to communicate results to co-investors or family members who may not be familiar with more complex financial metrics.

Best Times to Use IRR

IRR, on the other hand, becomes crucial when time efficiency is a key factor in your decision-making. It’s especially valuable for evaluating VC fund managers or investment strategies. For example, a fund consistently delivering a 25% IRR demonstrates better capital efficiency than one achieving a 15% IRR, even if both provide similar absolute returns. This makes IRR an essential tool for institutional investors allocating capital.

Another strength of IRR is its ability to facilitate cross-asset class comparisons. Whether you’re considering startups, real estate, or public markets, IRR provides a standardized way to evaluate risk-adjusted returns. For instance, if public markets are yielding 8-10% annually, a startup investment must show significantly higher IRR potential to justify the added risk.

IRR is also a key metric for portfolio construction. When building a diversified venture portfolio, it helps balance investments with varying holding periods. You might accept a lower IRR from a later-stage investment for its predictability while seeking a higher IRR from early-stage deals to offset the increased risk.

Using Both Metrics Together

Many investors use CoC and IRR together for a more complete analysis. While CoC measures absolute returns, IRR focuses on capital efficiency. Combining the two gives you a well-rounded view of an investment’s appeal.

Take this example: Company A offers a 5× return over seven years, while Company B delivers a 3× return in three years. CoC might favor Company A for its higher absolute return, but IRR highlights Company B’s superior annual efficiency (approximately 44% vs. 26%). This dual perspective helps you decide whether to prioritize wealth creation (Company A) or faster reinvestment opportunities (Company B).

Allied Venture Partners advocates for this combined approach when helping investors build diversified portfolios. By analyzing both CoC and IRR, you can balance long-term wealth creation with short-term capital efficiency. This strategy is particularly useful for angel investors aiming to mix high-return opportunities with faster-cycling investments.

This dual-metric approach is also helpful during portfolio rebalancing. For example, you might retain investments with strong CoC potential, even if their IRR is modest, while seeking new opportunities with higher IRR to boost overall portfolio efficiency. It’s a strategy that optimizes both total returns and capital velocity over time.

Using both metrics also ensures transparency with stakeholders, such as co-investors or limited partners. Presenting both the absolute return potential (CoC) and the annualized efficiency (IRR) provides a clear and comprehensive view of investment performance. This clarity helps align expectations around wealth creation and timing, making it easier to choose the metric that best suits your investment goals.

Choosing the Right Metric for Your Investment Goals

When deciding on the best metric to evaluate your investments, it all comes down to your strategy. Cash-on-Cash (CoC) return provides a simple way to measure the cash yield relative to your initial investment, while Internal Rate of Return (IRR) takes it a step further by incorporating the timing of cash flows to offer an annualized performance measure.

If your focus is on immediate cash flow, CoC is the metric to lean on. It gives you a straightforward snapshot of the return on the cash you've invested, without factoring in when those returns occur. This is especially useful for investors who prioritize short-term liquidity.

On the other hand, if you're aiming for capital efficiency, IRR is your go-to. It shines a light on investments that deliver the highest annualized returns, making it easier to compare opportunities with varying cash flow schedules. IRR helps you assess long-term growth potential and evaluate how efficiently your capital is being utilized over time.

For a well-rounded perspective, consider using both metrics. CoC captures the absolute cash yield, giving you clarity on immediate returns, while IRR focuses on time-adjusted efficiency, balancing short-term results with long-term growth. This dual approach ensures you're not overlooking either aspect of your portfolio's performance.

Allied VC advocates for this combined strategy, as it reflects the nature of our investments - some generating quick cash returns, while others grow steadily over time. By tracking both metrics, you can build a portfolio that aligns with your financial goals and investment timeline.

Ultimately, the choice boils down to your priorities. Whether you're drawn to direct cash yield or prefer to focus on time-adjusted growth, each metric offers unique insights. Pick the one - or the combination - that best aligns with your timeline, risk tolerance, and long-term objectives.

FAQs

When should I prioritize Cash-on-Cash Return (CoC) over Internal Rate of Return (IRR) in startup investing?

The decision to use Cash-on-Cash Return (CoC) or Internal Rate of Return (IRR) depends largely on your investment priorities and timeframe.

CoC is a go-to metric when you’re focused on immediate cash flow. It’s perfect for evaluating short-term returns, ensuring steady recurring income, or safeguarding capital in the near term. This measure is simple to calculate and gives you a clear picture of how much cash you’re earning in relation to the cash you’ve invested.

IRR, on the other hand, shines when you’re looking at the bigger picture - assessing long-term growth and overall profitability. By factoring in the timing of cash flows, IRR provides a more detailed analysis of an investment’s performance over its entire duration. This makes it a valuable tool for evaluating early-stage startups or projects where future growth and risk are key considerations.

In essence, CoC is best for short-term cash-focused decisions, while IRR is ideal for analyzing long-term potential and profitability.

What are the risks of using only IRR to evaluate startup investments?

Relying only on Internal Rate of Return (IRR) can expose investors to several pitfalls. One major issue is that IRR is highly sensitive to the timing of cash flows. Returns received early in the investment can disproportionately influence the overall performance, creating a potentially misleading picture - especially if those early returns don’t reflect the investment’s long-term potential.

Another limitation is IRR’s assumption that all returns can be reinvested at the same rate. This assumption is often unrealistic and can lead to overly optimistic projections. IRR also ignores the scale of an investment, making it tricky to compare opportunities of varying sizes. For investments with irregular cash flows, IRR can even produce multiple conflicting values, further complicating the decision-making process.

Because of these shortcomings, it’s crucial to pair IRR with other metrics - like Cash-on-Cash Return (CoC) - to gain a more balanced and accurate understanding of an investment’s potential.

Why is it helpful to use both CoC and IRR when evaluating a startup investment?

Using both Cash-on-Cash Return (CoC) and Internal Rate of Return (IRR) gives investors a more complete picture of a startup's investment potential. CoC zeroes in on the immediate cash returns compared to the initial investment, offering a snapshot of short-term liquidity. Meanwhile, IRR looks at the timing and scale of all cash flows throughout the investment period, providing a clearer sense of long-term profitability and growth.

When these two metrics are used together, they allow investors to weigh short-term returns against long-term value. This approach supports better decision-making and helps minimize the risk of missing critical factors in a startup's performance.